Overland, Olhão to Edinburgh: a photo blog (part two)

On to Vigo, San Sebastian – and Edinburgh

It’s raining as I slip out of the Porto guest house just after 6.30 a.m. on a cold, dark early February morning. There are only two trains a day north into Spain, and I’m on the early one rather than the late evening one.

I climb on board at Porto Campanhã , clutching my takeaway coffee and croissant from the station café. There’s just a few carriages and a few passengers. We’re soon on our way; the ticket man comes by and wishes me a good journey in Portuguese. With that and my coffee, I’m feeling good despite the early start.

I can mostly see out the windows, despite the multi-coloured graffiti that’s been sprayed over some of the train exterior. Beyond the outskirts, we start to pass by small towns, gentle hills and fields, mostly bare trees, there’s little hint of spring here.

In some of the fields, I spot the distinctive stone and wood granaries, small rectangular, storage places, that sit on stone legs, known as hórreo in Portuguese, which I remember from travelling through Galicia two years before. They are typical for northwest Spain and for northern Portugal. It reminds me that the northern part of Portugal also has Celtic roots, just as Galicia does.

Further north, on our just over two hour journey, the railway line runs nearer the Atlantic coast. Huge rollers are crashing onto beaches that are part sandy, part rocky. The train slows to cross the broad river estuary coming into the northern town of Viano do Castelo. There are large white egrets on the mudbanks, some rowers in a scull on the water.

Further up the coast, I glimpse beautiful sandy bays near Moledo before we turn east along the southern bank of the Minho river estuary that marks the Spain-Portugal border. It’s a wide, languorous river at this point, green banks on both sides.

The train is slowing but soon enough we’re heading north again into Spain (no border checks) and are pulling into Vigo, through its industrial outskirts and past its big, busy ports.

Vigo is a city of around 300,000 people with a small, old town and a graceful new town. It sits on one of the Rias Baijas. Galicia’s northern and western Atlantic coasts are respectively home to the beautiful Rias Altas or high or upper estuaries/inlets and the Rias Baijas, low or lower ones. I’ve explored the beautiful northern rias before but this is my first time on the west coast. Today, in the sun, the ria is sparkling blue, contrasting with the green, tree-lined banks.

It’s chilly but still sunny as I walk the 15 minutes from the station to my overnight studio. It’s down a narrow, dark alley near one of the churches in the old town, very central. I drop my bags and head out. It’s midday on a Sunday. People are spilling out of mass into nearby tapas bars.

I’m lucky enough to get an outdoor table in the sun at a busy taverna in a small square. I want lunch but first I order a sparkling water – even water, it turns out, comes with tapas of cheese and olives. It’s a good start. Then I order a selection of Galician cheese and some padron peppers. There’s a laid back but cheerful weekend atmosphere in the square and, apart from the cold breeze, I’m happy to take my time and relax – apart from avoiding the seagull that divebombs at one moment to snatch a piece of cheese off my plate.

After lunch, I head up to the ruins of the 17th century castle, the fortress of El Castro, that overlooks Vigo and the estuary, including great views out to the Cíes Islands’ nature reserve – another trip for my ‘another time’ list.

There are beautiful grey-green pine trees and views back down to the estuary as I climb the steep path.

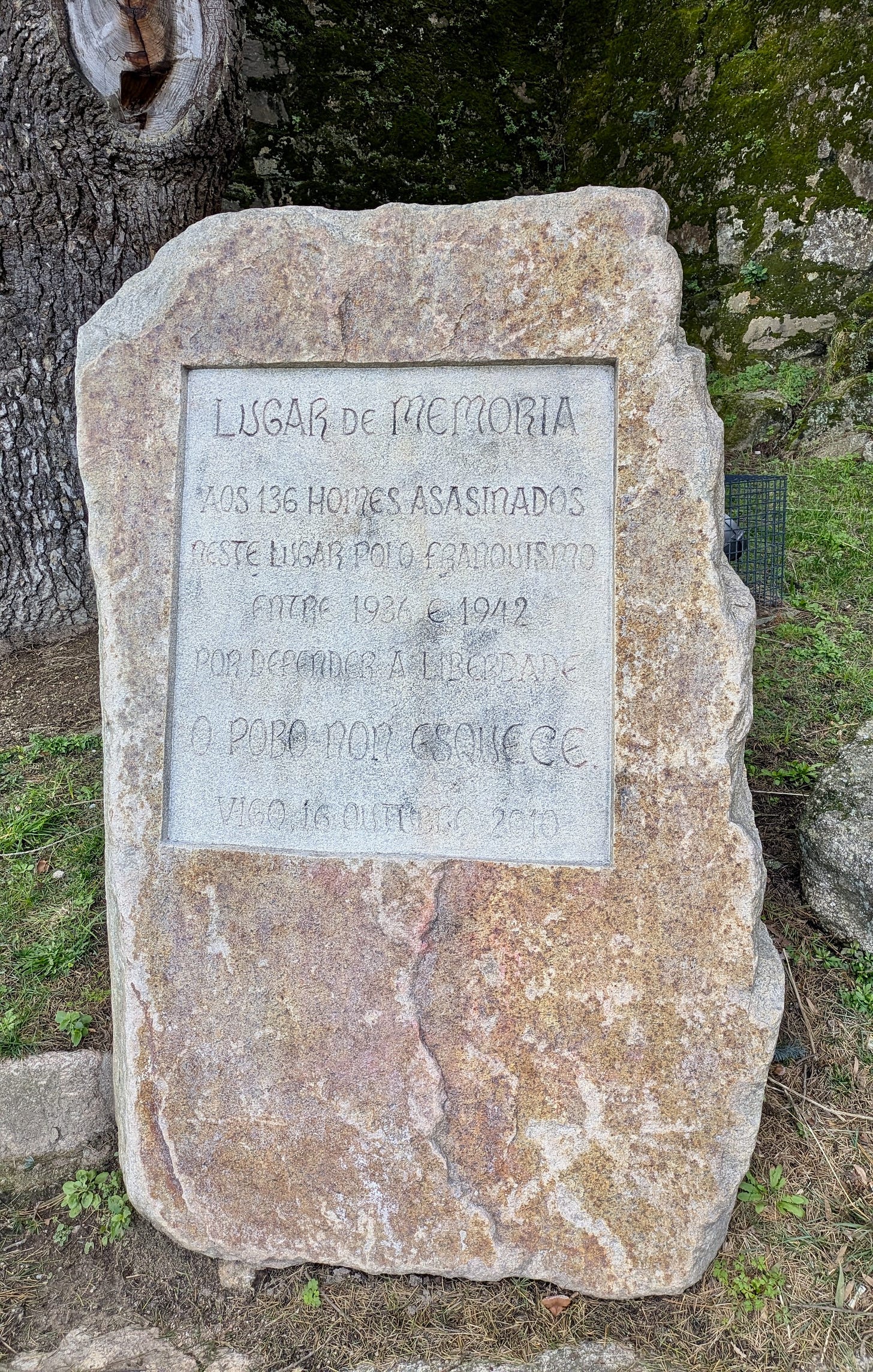

At the top, the ruins of the castle and its walls sit amidst peaceful greenery of trees, plants, lawns. But at the old castle gate, there’s a memorial stone, only erected in 2010, marking the 136 freedom fighters from the Spanish civil war who were killed there between 1936 and 1942.

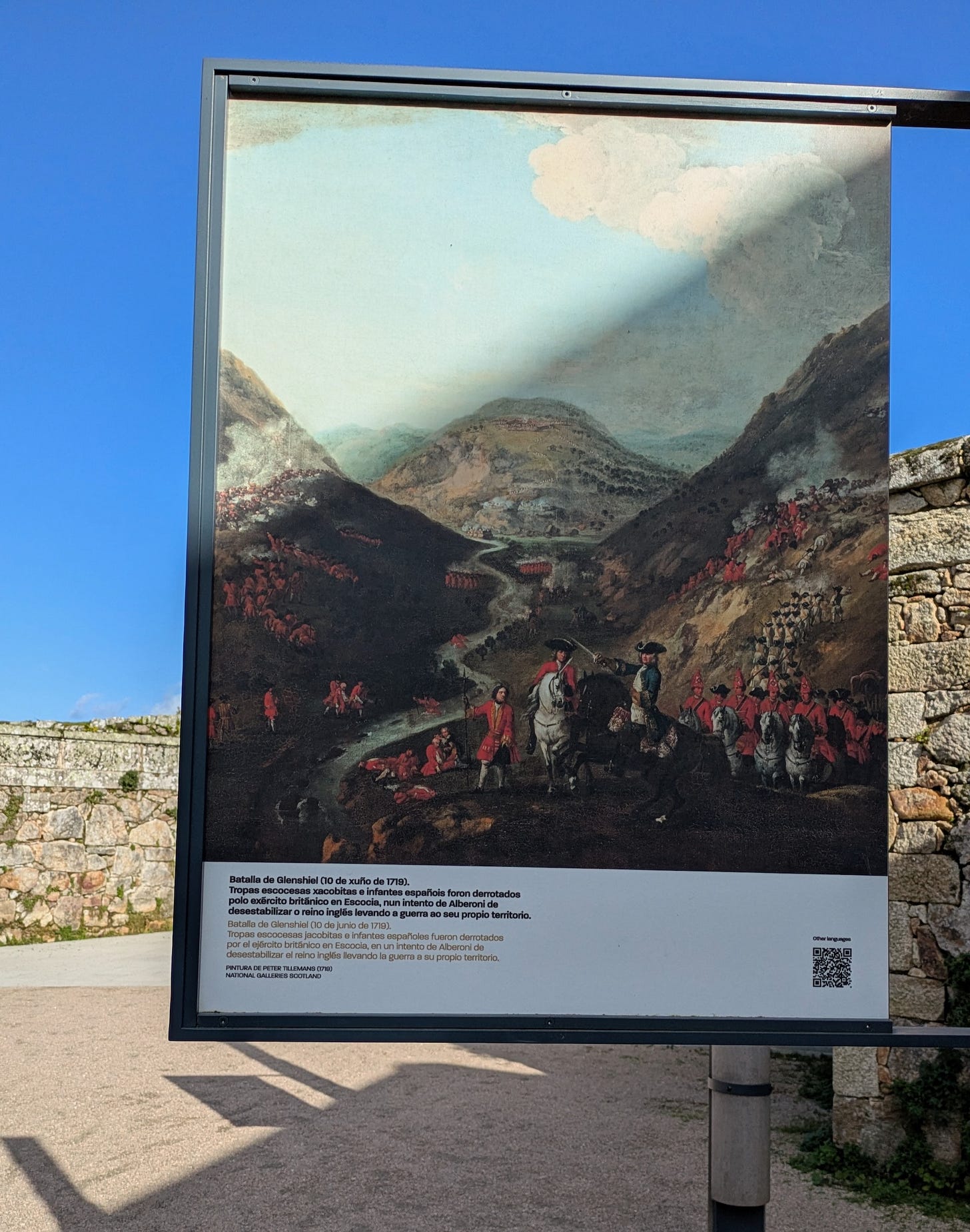

Further into the interior remains of the castle, I come across some billboards with prints on them of old paintings of English naval ships and then one of troops in a glen in Scotland. The explanation is all in Spanish. But it becomes clearer that these boards are marking the English invasion in 1719 that defeated the Spanish to take over Vigo, after Spanish troops had sailed to Scotland to support the Jacobites at the Battle of Glen Shiel. Spain had also taken over Sicily and Sardinia.

Spain regained Vigo after the Treaty of the Hague in 1720 (which ended the war between Spain and the ‘quadruple alliance’ of Austria, Britain, France, and Savoy). Complicated European politics and conflicts are not, as we know, a new thing.

Better informed, and musing about our intertwined histories, I walk back down to the old town.

Later, I head to a tapas bar specialising in local, fresh seafood for an evening meal and a glass of the local Albariño. The waiter is chatty and speaks good English. I apologise for my lack of Spanish but he tells me the Spanish speak worse English than the Portuguese as English language films are dubbed in Spain but sub-titled in Portugal. His good English, it turns out, is because he studied business at Edinburgh university – small world once again.

I head off to my studio flat, to get ready for another early start the next morning. It’s only been just over half a day, yet I feel I’ve seen a lot of Vigo, in a short time and learnt a little of its history too.

Towards San Sebastián and North

It’s dark as I leave the old town at 7 in the morning to catch my 7.45 train eastwards. Vigo is as far west as Portugal’s coast but Spanish time is an hour ahead of Portugal, so the sun doesn’t rise until almost 9 a.m., far south though we are.

Today’s journey is due to take 11 hours to San Sebastián, or Donostia as it’s called in Basque, with a change of train for the last two hours. The helpful station ticket office in Lisbon booked me into first class for the long first leg of the journey, as standard was full, they said; but it only cost around €65, not bad - and comfortable with it.

We head off eastwards towards the dawn but with such bright lights in my carriage that I can’t easily see out even as the pre-dawn light starts to filter through.

I discover that the café/restaurant car has gentler lighting so I head down there to watch the dark outline of the Minho river emerge into daylight, mostly bare trees lining the banks and hills that the river winds through, mist sitting on some of the hills or rising from the river.

It's a modern Spanish train but we seem to be going at about 50 kilometres an hour – it’s because the track weaves around following the river’s curves. I wonder how we will get to San Sebastián even in 11 hours, we’re going so slowly. Three hours and 250 kilometres after we started, we pull into a town called Ponferrada that sits on the Sil river. The sun finally emerges from the morning mist and cloud. We continue on our slow journey through higher, green mountains and hills, following another river valley, there’s occasional glimpses of snowy mountains to the north, sometimes close by, mostly in the distance. At one point there’s even snow on the railway embankments as we trundle by.

Eventually, we descend to the plains. I had thought maybe to head north to take the small narrow gauge railway that runs along much of Spain’s northern coastline. But I’d dropped the idea though I see now that the route to take the coastal train would have been to change at León (where we just arrived), and head north to Oviedo. One day, I say to myself.

The train suddenly starts to show what it can do as its speed heads up to over 200 kms an hour. So, the journey can be done on time. There are more snowy mountains to the distant north, including the Picos de Europa – a visit to Asturias definitely beckons.

Finally, after almost nine hours, and with the train slowing down again as the terrain gets hillier, we approach the industrial city of Vitoria-Gasteiz, the capital of the Basque country, where I change trains. Except, as it turns out, the train to San Sebastián is cancelled so there’s a replacement bus.

I clamber on board. The bus driver is telling us all something in Spanish. I’ve no idea what – though I do catch ‘no comer’ so I put my crisps away – but as long as I’m on the right bus, that’s ok. And, in fact, the bus trip through the green hills, and rather grey and industrial-looking towns, of the Basque country ends up being a bit faster than the train would have been. We’re deposited at the main train station in San Sebastián, and once I’ve found my way over the high, red metal pedestrian bridge towards the city centre, I’m soon at my cheap, simple, clean pension on a pedestrian street on the edge of the old town.

A day in San Sebastián

I’ve two nights but just one day in San Sebastián. And then, from here, I will head north to Paris and on to London all in one day. Distance-wise, San Sebastián is almost halfway back to Edinburgh. But having taken a slow and winding route of over a week this far, a day and a bit to Edinburgh is going to feel rather sudden and speedy.

I’ve got used to travelling, to its ups and downs, arrivals and departures, stimulation, exploration – albeit sometimes as much a sense of fatigue as of movement and discovery. I feel I could keep going, adapting to being on the move as a way of life. Home seems a long way away. Yet, suddenly, it’s getting nearer again.

But for now, I plunge into exploring San Sebastián. I was here just once before, decades ago, as a young researcher, attending my first overseas conference.

I have memories of La Concha, the golden circular beach and bay and the elegant apartment buildings surrounding it, including the iconic hotel de Londres. On revisiting, it doesn’t disappoint.

It’s much wintrier here, chilly, bare trees, people wrapped up in warm coats. My slow travel home is gently but determinedly reacquainting me with northern winter after the more spring-like feel of Portugal. Yet the city has a bright and relaxed atmosphere.

There’s plenty of people strolling round la Concha in the evening, with lights glittering around the circular bay until the land meets the darkness of the Bay of Biscay on the horizon. The old town, though, is quiet on a Sunday evening in February when I venture out to find some tapas for dinner.

In the morning, I head back to la Concha. There’s a high tide. White-tipped waves are rolling in to the small part of beach still visible.

I lean on the white metal balustrade watching the swirling power of the waves. The sun is still low in the sky, hidden behind the buildings but some sunbeams find their way along the side streets and streaks of light hit the beach and waves, shadow and light mingling.

An old woman says something to me in Spanish or Basque. I say something back in English and she cheerfully talks to me at length, waving her arms. I don’t know what she’s saying but my guess is she’s saying isn’t it beautiful and that she comes here every day. I nod, smile. Communication doesn’t have to be clear to be good.

I walk down onto the quiet beach. A man is carefully inscribing a slogan in the sand. A couple of swimmers are braving the early morning waves and there’s a couple of dog walkers – the beach still mostly covered by the incoming tide. When I walk past again an hour later, the sun is fully up, the tide is going out, the sea calm and the beach busy. I’ve caught it early and at the perfect moment.

I find a café/bar for breakfast in the new town. There are a few locals inside, mostly having coffee or beer with a slice of tortilla. I have coffee and a croissant - tortilla can wait.

Then I take a long, bracing walk along the seafront to the next bay watching the powerful Bay of Biscay rollers crashing in against the rocks.

Later, in the afternoon, I find my way to the San Telmo museum, walking across the old town.

The museum is in a 16th century convent building but with a modern extension. And it houses the museum of Basque society and citizenship. I chat to the young man at the ticket desk - then I make my best effort to say ‘thank you’ in Basque - eskerrik asko - which I’d learnt the day before. He smiles broadly and so do a couple of the nearby security guards. The museum turns out to be a fascinating mixture of old and new, the evolving and often turbulent history of the Basque country and nation. And the goal of independence remains a core part of its politics.

Later, I head to bar Nestor for tortilla. It proudly displays a faded newspaper saying it won a ‘best tortilla in the world’ championship some years back.

These days you must book ahead for a slot at the bar to get some of the famous tortilla. It comes out in a big, yellow round that the barman rapidly slices up with a large knife and hands out.

It’s great tortilla but the limited menu and the tourists lined up for their slot mean there’s little atmosphere. I chat briefly to a young woman from Singapore. She’d flown to Paris, flown on to Bordeaux, then hired a car and was surprised when I explained there’s a train from San Sebastián to Bordeaux and Paris. So much, I muse, for France’s welcome new law that limits short-haul flights where a train can do the journey in two and a half hours – I guess it doesn’t apply to domestic flights connecting to international flights.

Out in the streets of the old town, there’s a quiet but warm atmosphere. Suddenly, there’s singing and a procession of people dressed in traditional garb come by – celebrating what I don’t find out. But it’s a sudden splash of sound and colour.

My journey is heading towards its final stage. I walk back to la Concha. The lights sparkle on the edge of the bay.

To the west, there’s a half moon, with Venus below it towards the horizon, shining over the dark sea. Then I head for my guest house. One more early start the next day.

San Sebastián to Edinburgh

Before 7 a.m the next morning, I’m walking through San Sebastián new town to the station then grab an early coffee at the crowded café there.

My route, finally back to the UK, means I need to hop on a local, metro-style ‘Euskotren’ train that takes me over the border to the French town of Hendaye (credit due again to ‘the man in seat61.com’ for the clearest of explanations of this simple trip). Soon enough the short train journey is over, crossing the Bidasoa river that marks the border, and I’m in plenty of time at Hendaye, and its dusky pink train station, for my 5 hour TGV ride to Paris.

The TGV is busy, stopping at various towns at the start of the journey to take on more passengers, before rattling at high speed through the French countryside. I’m definitely back in a winter zone now.

Geese are pattering around in a frosty field as the train passes; there’s low sun light shining onto the stubble of a wheat field, the Ardour river is languidly winding past as we draw into Bayonne.

After Bordeaux, I have a decent lunch in the buffet car, watch the broad, rolling countryside fly past. After Tours, more grey and misty weather flows in and lingers all the way to Paris.

I’m thinking again about travel and our mad flood of summer flights decanting south for our bit of sun. But if thousands of people switched to trains for the annual southern holiday rush, they’d be overcrowded too even though more climate-friendly. And so many places depend on tourism economically even while it creates problems from climate to housing and more. We can travel less and better, but it’s a systemic problem too as our politics half tackles, half steps back from tackling the climate and biodiversity crisis with the urgency and scale needed. And it’s more than that too, of course. It's about how we live as part of our planet not treating it as a playground.

As I reflect, the train is hitting the grey, misty Paris suburbs. I’m still not feeling ready for this return. I leave the train, get on a metro from Gare de Lyon to Gare de Nord, and then go through my first passport checks since I left Faro.

The Eurostar is busy, my most expensive ticket of my journey (just for standard class), and my journey’s end is closing in. The carriage is crowded and feels cramped. But I soften the edge of my return, staying with a friend in London for a night, telling traveller’s tales over a glass of wine.

Soon enough, I’m at Kings Cross for my final train ride up to Edinburgh.

There’s some welcome sun as we leave London, then hours of mist and fog, the bare branches of trees coming in and out of focus, some sheep and horses in misty fields, a reflective journey. At Newcastle, the sun re-appears, the North Sea is sparkling for that final beautiful coastal run into Edinburgh.

I walk out into Princes Street gardens in the sunshine, take a selfie against the castle. I’m home. There will be time to reflect some more on travel, on our interconnected world – its land and ocean - on the folly of borders, on my particular memories of this 2,000 mile journey from my start in Olhão to the end of my journey in Edinburgh.

But for now, it’s over and I take with me, for a while, the sense that I now live in a larger and more connected space.

"Communication doesn’t have to be clear to be good"... Perfect. You obviously have the knack, Kirsty! Once again an enthralling read. Thinking of the Spanish waiter being a former student at Edinburgh University - I guess it might have been easier for him in the days before 2016. I'm heading next weekend to another university town, Leiden (Netherlands) which was once popular with Brits. My two sons are taking me for an 80th birthday treat!

Thank you for sharing the second part of your journey.

As a Scottish ex-pat living in Romania for the past 15 years, I thoroughly enjoyed the last 2 posts.