There’s a fine drizzle blurring my view as I stand watching the boats in Faro harbour before I turn, a bit reluctantly, towards the bus station. It’s late January, and after a fortnight in the small fishing port of Olhão, I’m on a slow, 2000 mile journey home to Edinburgh by train and bus.

I’ve neither planned nor booked my route home. But I have chosen Lisbon as my first stop. And, since there’s a possible train strike, I’m on the cheap, comfortable express bus out of Faro – which also turns out to get to Lisbon faster than the train. The bus driver speaks English as well as Portuguese and explains to me we’ll stop halfway for a loo and coffee break. The bus isn’t full, and once we’re on the motorway, it’s quiet, not much traffic, as the bus heads north through the Alentejo region.

The road winds past orange orchards and other trees already vibrant with pink blossom; and on it runs through green hills, bare fields of rich brown-red soil, flatter, drier scrub land and big, broad valleys full of grey-green pines, cork trees, olive groves, birds of prey circling overhead.

There are few villages visible from the motorway, but occasional large white farmhouses, orange-tiled roofs, stand out in the landscape. I glimpse a herd of cattle driven, by a man leaning on a big stick, across distant fields. The sky is blue with huge, tall, almost circular fluffy clouds suspended over the landscape.

As the bus heads on its way, I’m thinking about travel, that human urge to be on the move, to explore. But when did we all start to think that beaming ourselves up in planes was the best way to travel, hopping from place to place with little idea of the places, people and countryside in-between? And why have most of us, myself included, been so slow to cut back on, or even quit, flying in the face of the climate crisis? There’s a deep and unhelpful sense of entitlement in so many of the ways we choose to live, not least in how we travel.

As my journey unfolds in the days ahead, I reflect back on Brexit too as, from Portugal to Spain to France, I am never asked for id or passport until I board the Eurostar in Paris. Our connected European continent may have borders marked in across it; and culture, politics, language and more all change as I travel. But it’s also so clearly part of one interconnected, overlapping, if diverse, geography and society too; we are contiguous, connected.

My musings are interrupted by the halfway stop, and after a quick espresso in a modern, efficient service station, we’re on our way again. And soon, in under three hours, we’re high up crossing the Ponte 25 de Abril, the famous, red suspension bridge taking us from the southern to the northern banks of the Tagus. Shortly after, we reach the bus station and I switch to the metro heading downtown to find my home for the next few days.

Lisbon days

I’m staying in the Santa Catarina neighbourhood just up from the Bairro Alto – a little further down the hillside is the flat, 18th century, elegant central grid of Chiado. I’ve booked a small, second floor apartment. One of the hosts meets me and while showing me round explains only two of the eight or so apartments in the building have local residents in them. He adds that they’re not allowed to have more rental licenses in this district – too late it would seem given such an imbalance. Airbnb and other short term lets have become, rightly, very controversial in Lisbon, as accommodation becomes hard to find and too expensive for most locals, not least younger people. And the imbalance in this building makes me think it’s now better to stay in a guest house or hotel, though that’s only one part of tackling overtourism.

As the sky gently fades towards sunset, I walk down the steep narrow street I’m staying in, then up another, equally steep, lane and soon I’m having an aperitif at the Santa Caterina viewpoint, watching the sun go down behind the red, 25 of April bridge, seeming almost to compress its golden globe into the horizontal truss of the structure. There’s plenty of locals there, and just below the outdoor café I’m in, there’s a small terrace where someone’s busking, groups of young people sitting around listening.

Later, I pass a local eatery, packed and chaotic-looking on a Saturday night. The jammed together tables are all full but there are places set for dinner at the bar too. A couple of TVs are showing a match between two local Lisbon football teams. The waiters are managing to serve everyone while keeping a clear eye on the screens. I chat a little to an old man sitting next to me. He asks where I’m from, so I say Scotland and add that it’s Burns’ night, explaining he’s a poet. The man points out this taverna is just up from the Praça Luís de Camões, Portugal’s national poet – there’s a statue to Camões in the square too. Connecting cultures. He leaves before me, puts on his cap and laughs as I spot that it’s got a tartan pattern.

I’m back at the Santa Catarina viewpoint the next morning, quieter now, hazy morning sun glinting from the east. At the café, I chat to the young Brazilian waiter who tells me he backs Portugal in football, except if Brazil is playing – fair enough.

My days in Lisbon pass quickly. The weather is mixed, with a lot of sudden downpours. One day, rising fog obscures the Tagus for half the day, reminding me of the haar back home. Then, sometimes the sun reasserts itself, and roofs, terraces, the estuary all suddenly glisten. It’s the end of January, but Lisbon is full of tourists – and yes, I’m a visitor too. But I can’t help but think again about the madness of overtourism that blights countries and cities around the world including the problems here in Lisbon and back home in Scotland.

When it’s not raining, Lisbon’s winter light is beautiful, hazy white and slanting, casting shadows and giving a hint of warmer days, not yet but before long

Over the days I’m here, I visit some old and some new haunts.

The Moorish St George’s castle always draws me back with its atmosphere of centuries past and its stunning views. And the modern art museum is another place I return to, both for its mixture of buildings from different centuries and its exhibitions.

But, as often as not, Lisbon is a place simply to wander, to get lost in a little, or to pause in a street café, take in the sense of opening up that sitting outside in winter can give you.

Soon enough, I have to decide where I’m moving on to. My thoughts of visiting a Portuguese rewilding group based in the Côa valley, founder on my lack of preparation – another time, we agree. So, one morning, I walk through the back streets to Santa Apolonia station to book my train tickets to Porto and beyond in person. There I’m helped by a patient, friendly man in the ticket office, who first sorts out my Porto ticket, then one over the border to Vigo in Galicia, north-western Spain, and then an 11 hour journey, for some days’ time, which will take me from Vigo in Spain’s west to San Sebastián right by Spain’s border with France.

I had considered and abandoned the option of travelling from Lisbon to Madrid, then on north from there. But at 12 hours travel, and with two changes, I decided (having scrutinised options on the always helpful ‘man in seat61.com’ European and international train website) that it would have to be a journey for another time. The shortest way home from Faro would, it turns out, have been a bus over the border to Seville and by train from there via San Sebastian or Barcelona. But I’m happy with my more winding path home.

I walk back from Santa Apolonia, my tickets in my bag, up through the steep, narrow streets of Alfama, away from the touristy thoroughfares, when I spot a small café, sun shining into its open doorway and onto a table just inside the door. I go inside, and sit at the table, catching the gentle winter sun. The young woman barista is friendly and tells me she also sings fado and plays guitar; she plays me a beautiful tape of her music.

And then a friend of hers comes by, also a fado singer, Brazilian, who takes a guitar off the wall of the small interior and starts singing some deep, moving and emotional songs, all written by her, for the next half hour. The singer, her braids falling to her waist, is wearing a sea-green top, the same colour as the scarf I have on we agree – and that prompts her to tell us it’s an African day for forests and animals, marked by the colour green. Then my barista friend picks up the guitar and sings too, simple and compelling. The first singer turns a circle on the pavement outside, almost dancing in the welcome winter sun, then leaves.

I, too, move on up the hill, saturated and uplifted by the music and friendship of that unplanned moment.

North to Porto

A couple of days later, I’m on the morning train to Porto.

After it clears the industrial outskirts, the train chugs along comfortably past flat, water-logged, misty fields that give way to green rolling hills, often tree-covered, the ubiquitous eucalyptus, pines, and with occasional glimpses of villages, white houses, orange roofs, jumbled together. The train rolls along beside a big river. It’s the Tagus and around here it has overflown its banks into the surrounding fields, while horses stand at the edge of the sparkling water occupying half their land. I glimpse white birds in fields further off – egrets, or storks maybe? Many of the trees are still bare; winter is not over yet but occasional orange trees stand out, already full of fruit.

We arrive into the main Porto Campanhã station where I change to the smaller local train that soon drops me at the central, grand, blue and white-tiled station of São Bento.

It’s a ten minutes’ walk to my guest house – after finding my way around the long-running building works for a new metro line through the centre. The reviews said my guest house was in a pleasant, peaceful area. But it’s near a busy road, there’s a big hospital across the way, my spirits sink. But the inside is a tardis-like revelation: a large and grand 19th century merchant’s house, with a beautiful, curving staircase, decorated walls and ceilings.

The man on reception is friendly and helpful – we chat a bit, about the house, about the state of the world, the need to cling onto hope (we’re less than two weeks into Trump’s presidency at this point). And then I climb three floors up to my large, comfortable room which is at the top of the house, with a balcony looking west over gardens, perfect for a sunset view.

I’m only here for two nights so I soon head out.

I walk downhill, through a park, along narrow, winding lanes and down flights of steps towards the river.

Across the Douro, lie the distinctive buildings of the port company warehouses; boats in the style of old port barges – now mainly for tourists – dot the river.

As dusk falls, I sit with a glass of wine outside, near the river’s edge, looking up towards the Dom Luís I Bridge, the iron, double-deck, late 19th century bridge that spans the river.

A cormorant flies low skimming the river’s surface.

Later, I eat in a fish restaurant in a busy set of narrow streets, full of cafes and tavernas, their outdoor terraces full of young people chatting noisily. It’s good food in my taverna but full of tourists even at the start of February.

The next day, I wander Porto’s narrow streets.

It’s more medieval than Lisbon, less disrupted by the earthquakes and fires suffered by Lisbon two to three hundred years ago.

I find myself at a local market on the Praça Carlos Alberto. One stall has rather eccentrically cute, large china dog statues for sale. They remind me of a china tiger my parents once bizarrely bought.

The young woman on the stall tells me that such dog statues used to be a typical thing in family homes many decades back and, now that generation is passing on, she tries to rescue and repair them when house contents are up for sale. But no, she’s not heard of china tiger ones. I find a table at a café on the market edge, enjoy the brief bit of sun before cloud returns.

On the same square, I find a museum called the Banco de Materiais (Bank of Materials). The young woman working there explains to me it’s a repository of thousands of azulejos tiles which it not only collects and stores but then also gives to owners of houses and buildings to use in restoration. And it’s open, too, for visitors like me, just to wander round the shelves of tiles and look at the colourful and diverse decorations of the old tiles. It’s an original and optimistic approach to protecting and keeping a vital part of local and national Portuguese heritage and culture.

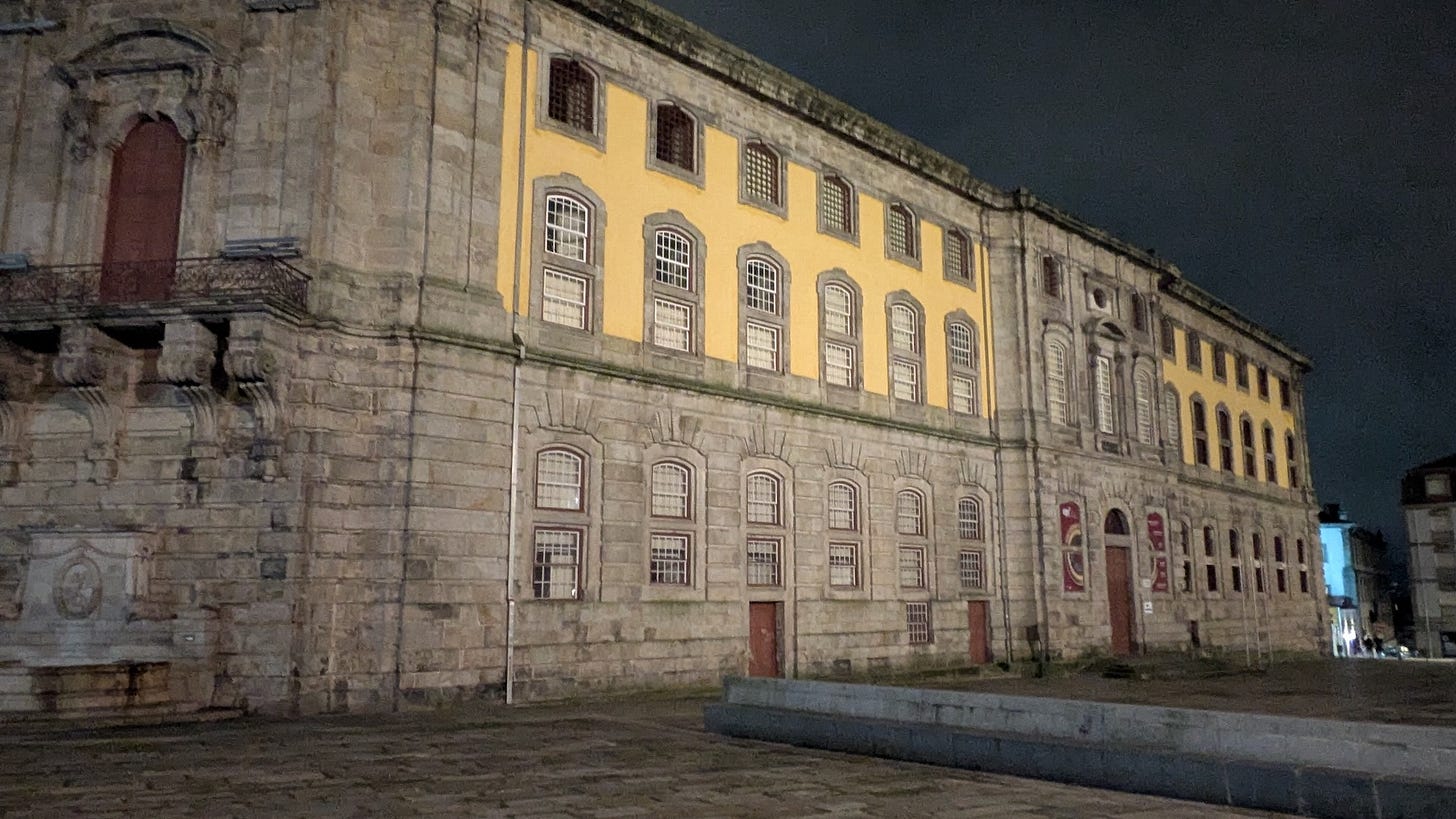

Next, I drop into the Portuguese Centre for Photography, housed in an imposing 18th century building that was used as a jail until Portugal’s 1974 revolution that established a democratic state. On the top floor is a collection of hundreds of cameras from down the decades and centuries even. Our urge to record, to capture is fully captured here.

Further down near the river, I visit the 1325 customs house and mint, celebrating its 700th anniversary this year. Beneath the old walls of the house lie even older Roman remains, including visible parts of floor mosaics.

The young man on the ticket desk talks to me about its history and an argument between the Portuguese king and Porto bishop 700 years ago over who got to get the revenue from customs duties, shades of Trump today – mad kings and arguments on tax, have we progressed at all, I wonder.

Later, I eat clams with a glass of white wine by the river’s edge, the coloured lights from the bank opposite reflecting in the Douro, then back to my guest house, ahead of an early start in the morning.

Glaswegian couple living now on Spain's Costa del Sol. Your description of Porto has me looking at Ryanair for a cheap flight there from Malaga. Nicely written

Beautifully photographed (and written)... You make the reader (at least in my case) feel what you were feeling. I enjoyed the subtle nods to the Forth Road Bridge too! Maybe now that I'm on my own I'll pick up the courage to travel like you do, instead of vicariously. Who knows. "Travel for the solitary 80 year old" maybe! :-)